We continue our series of posts about the expedition to Lodge Hill, Kent, with this from Historian Dr. Richard Baxell.

Testament of Hoo

You may never have heard of the Hoo Peninsula. I imagine many people living outside the south-east of England haven’t. You might, however, have come across it under the name ‘Boris Island’, which some media wit came up with following a proposal by the former London Mayor that the area would be an ideal site for a new London airport. To the relief of many, not least many local residents, Boris Johnson’s controversial plan was never realised, condemned in an Airport Commission report for being too costly, environmentally problematic and hugely disruptive for local businesses and communities. Nevertheless, despite widespread criticism – and no small amount of ridicule – Johnson remains keen on the project. Whether, assuming that he replaces David Cameron as Prime Minister, he will work to reinstate the plan, is anyone’s guess. It is just one of all too many ‘known unknowns’ that could follow last week’s Brexit.

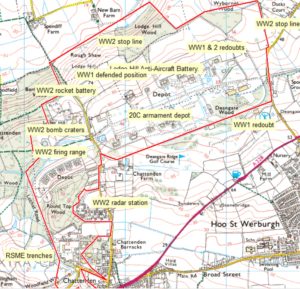

Lodge Hill historic sites © Ordnance Survey

Whatever happens, the Hoo Peninsula is likely to continue to face issues of development. Lying on the new fast train line from Ashford International to London, the local station at Strood is only 30 minutes from St. Pancras. Since the completion of the new line, locals have noticed steep rises in house prices. Developers circle, eager to make a killing

provide urgently-needed affordable new properties. The latest area identified for development is an old military site at Lodge Hill, just north of Chattenden which has been designated by Medway Council as a ‘brownfield site’ so, on the face of it, a perfect place for new houses. However, many locals and conservationists believe that the intrinsic value and unique importance of the area has been seriously underestimated. Last year’s designation of the area as a Site of Special Scientific Interest by Natural England, the government’s environmental protection agency, might suggest that they have a point. The presence of a unique unspoilt habitat, in particular one of the country’s most important populations of Nightingales which, so proponents of the scheme claim, could be safely moved twenty kilometres away to new grasslands in Shoeburyness, Essex, has met with strong opposition from environmental campaigners and the issue has been picked up by the national media.

Access to Lodge Hill is restricted © Richard Baxell

So, on 16 June 2016, I took part in a site visit to Lodge Hill, organised by the charity, People Need Nature. I was just one of a large group, including photographers, journalists, writers, poets, conceptual and sound artists, ecologists and entomologists. Led by ecologist, environmentalist and serial blogger Miles King, the purpose of the visit was not to come down on either side of the debate (though most of the participants were probably sympathetic to the conservationists’ arguments), but to record and catalogue what remains.

A survey of the plants at Lodge Hill tells us how it is changing. © Catherine Shoard

We quickly discovered that entrance to the site is normally forbidden. This, of course, added a little frisson of excitement. So too did the health-and-safety briefing given by the gatekeeper on our arrival, warning of the numerous types of unexploded ordnance we could encounter and suggesting mildly that we probably shouldn’t stray too far from the path. There’s nothing like the potential of one’s imminent demise to heighten the senses.

Suitably alarmed, we spent a long day wandering around the site, carefully (watching where we placed our feet and) surveying the astonishing diversity of flora and fauna, a consequence of years of isolation. It’s an ecologists’, environmentalists’ and conservationists’ heaven. At one point the glorious singing of the famous Nightingales could be heard, to the delight of all.

From the perspective of a historian, the area is particularly fascinating. The Peninsula and its environs has long been important strategically, overlooking both the River Thames, route to England’s most important city, and the River Medway, home of the Royal Navy since the time of Henry VIII. Castles, towers, hill-top beacons, gun-emplacements, river barriers and a plethora of defensive fortifications are scattered liberally, maintaining guard over the rivers and the Peninsula itself. In the late Nineteenth Century, Hoo was chosen by the Navy as the site for a number of huge depots of munitions and explosives. One of those facilities was Lodge Hill.

Just as the military and naval history of Britain is written across the Peninsula itself, Lodge Hill is a microcosm of Hoo. Disused military buildings and former munitions storage facilities litter the site, including the remains of one of the country’s first Anti-aircraft batteries (scheduled under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979 to be of national importance) and First World War trenches constructed by the Royal Military Engineers, which were at the centre of military technology experiments in trench design and warfare. While many remains date from the First and Second World Wars, there are also sobering reminders of more recent conflicts: rows of terraced houses set-dressed to help train British soldiers in urban warfare. One was clearly designed to represent a street in Northern Ireland, the second a (rather less accurate) depiction of somewhere the middle-East, Basra perhaps. The attention to detail was astonishing, right down to pro-IRA murals on the end of the terrace and posters extolling the virtues of Osama Bin Laden.

Defaced poster of Osama Bin Laden. © Richard Baxell

After even a short time wandering around the site, it’s difficult not to come to the conclusion that much of Lodge Hill should be considered for conservation. With the property developer, Land Securities, abandoning their plan to build 5000 houses on the site, perhaps this is a good moment to take stock and evaluate seriously its potentially unique value, both as a testament to the nation’s past and its all too rapidly diminishing natural environment. The fate of the development now lies in the hands of central government. Unfortunately for the residents and environment of the Hoo Peninsula (not to mention everyone else), who that will be and what they will do is presently anything but clear.

The re-imaginers. L to R: Norman Crighton (back row), Marion Shoard, Jane King (back row), Gill Moore, Catherine Shoard, David Cox, Keith Datchler (back row), Julian Hoffman, Miles King, Richard Baxell, Matthew Shaw. Photo ©Steven Falk

Comments are closed.